Creating Online News with Storify

Posted by Dan James in Original story, Tools of the trade on October 12, 2012

Storify is a relatively new addition to an online journo’s toolkit. Essentially, it’s a free online program that allows users to easily trawl various social media websites for comments, photos and and other material on any particular topic. Just plug in your search term and away you go. Once you’ve found a post or photo you think is relevant, you just drag it into your story.

Poytner Institute associate editor Mallary Jean Tenore has made a list of five different types of stories that can benefit from the Storify treatment – social movements (e.g. Arab Spring protests or the Occupy movement), breaking news, internet humour, reaction stories (public reaction to news events) and the weather.

Those who read my Brisbane Zombie Walk story will notice I used Storify to create the photo gallery at the end. In fact, the story was actually written in Storify and then exported to this WordPress site. While my story was neither breaking news or about a social movement, I still felt Storify would be a good tool to use.

As my story was written before this year’s event, and I didn’t attend last year’s, I would have been unable to create a photo gallery the traditional way (or would have had a much harder time). However, a photo gallery (of some sort) was needed to liven up and help tell my story and Storify allowed me to go back in time and collect some interesting photos to use.

Unfortunately, while it worked out in the end, I’m not 100 per cent sold on Storify (yet). It is definitely useful, I just feel it needs a bit more development work

The Storify Positives:

1. The program was pretty easy to use

Storify will search a wide range of social media (Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, Instagram etc) and a few simple keywords will pull up lots of results. You can also search for a specific user/ username on the above media sites. It also allows you to filter or search only for photos or information which have been released under a Creative Commons licence (this was very important for my story, to avoid copyright issues)

2. Published Storify creates a permenant record

All the media and photos you add to your story are actually copied into, and stored in, the story itself. If a social media user later deletes one of their Facebook posts or photos, it will still show up in your Storify. No hiding!

The Storify Negatives

Unfortunately, I ran into a few problems, which leads me to believe Storify still needs some development work.

1. It’s still a bit glitchy

The “Save” and “Publish” buttons frequently froze (if that’s the right word) and stopped working. I had to restart the story a couple of times because these to functions just wouldn’t work. My attempts to embed the Google map didn’t work either (despite carefully following the easy instructions). I needed to leave space for it and then embed it in the WordPress version of my story (once it had been exported).

2. It doesn’t export to WordPress nicely (or easily)

It also took a while to to export my story to WordPress properly. Also, the instructions for posting a story to WordPress are out-of-date. The FAQ tells you to set this function up under the “auto-post” function/ menu. As far as I can tell, this doesn’t exist anymore. To export your story to WordPress, you need to:

- Publish your story

- Once published, at the top of the story, there will be three buttons – Export, Edit and Delete. Select Export

- Tell Storify you want to post to either a self-hosted WordPress site, or one hosted on WordPress.com. Fill in the required details (site address and login details) and then tell it to export your story

- Pray it works properly!

There is a (free?) WordPress plugin that you can download, which allows you to create a Storify post from your WordPress dashboard, but it currently only works with self-hosted WordPress blogs. Annoying, as I though WordPress.com hosted ones would have been more common.

3. No choice of fonts

The default WordPress font is ok (not sure what it actually is), but it would have been nice to have a choice.

4. No ability to (properly) preview photos and posts

Particularly when looking at photos, the search results box crams so many into the one area that they become tiny and hard to make out. I had to add them to the story just to get a proper look.

5. Creative Commons filter doesn’t catch everything

While the creative commons filter was handy, it didn’t pick up all the creative commons material available – only about half the photos I used were found in a Creative Commons search. And again, because it only shows you a tiny version of the photo, I needed to add images to my story and then click through to the original Flickr stream to see if the author had made it available under Creative Commons.

Please note – many of the above “faults” might not actually be problems. My inability to use technology properly without half a dozen manuals and serious advanced planning might have had some impact…

The Storypad Bookmarklet

I found this little feature to be Storify’s saving grace. Drag the bookmarklet into your taskbar and it adds a permenant “Storify this” icon. Then, next time you’re browsing social media and you see something that would work in a story, simply press the icon and a Storify tool is added to the page itself. You can then Storify that post or photo and it will be saved to the user’s “StoryPad”, easily accessible next time you “create story”.

I used this feature for about half my photos. I knew a particular user had released their images under a Creative Commons license, but they weren’t coming up in the search results (or were buried in the hundreds of results). This feature allowed me to go straight to their Flickr account and add content. So a great little tool if you know exactly where you want to look, or you stumble across something interesting.

So there we go – my brief look at Storify. A useful little program, but with the potential to be a lot better (if they just ironed out the glitches…)

Brisbane Zombie Walk festival lurches to new site after South Bank problems

Posted by Dan James in Original story on October 7, 2012

-

-

Source: garykemble’s Flickr stream

-

Source: garykemble’s Flickr stream

-

No zombies for South Bank

The move to Victoria Park is another major change for the Zombie Walk.

Mr Radaza says the Queensland Police Service advised an alternative route was needed after record event numbers at the 2011 Zombie Walk caused severe traffic congestion in the CBD.

“We expected 5,000 and ended up having 20,000 people.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t expect that and the police didn’t expect it either and the flow of traffic didn’t go so well,” he said.

However, plans to hold the Walk and festival at South Bank fell through after logistical issues arose.

A South Bank Corporation spokesperson said, in a statement, that the event exceeded the Cultural Forecourt capacity, their largest space available for venue hire.

But Mr Radaza says while the Walk itself was rejected, using South Bank as the festival venue was a “completely different issue” and he feels like South Bank was pushing them out after originally giving the event the “green light”.

“The thing that really got me riled up was that we paid for our deposit earlier in the year.

“They only got back to us a couple of months after and they’d decided ‘well, hang on, Zombie Walk… maybe it’s not the kind of charity we’re willing to take on’.

“They should have read the proposal before they asked for our money,” he said.

Mr Radaza says South Bank had issues with the zombie theme and did not want the festival’s main act because of “lyrical content” and musical style.

“I was getting a lot of negative vibes… things like ‘oh, there’s going to be a lot of blood there, and there’s going to be this and that’,” he said.

“They decided ‘we can’t have your main act’ because they considered it ‘doof doof’ music.

“But it’s a family event… they’re a very commercial group, young kids love them, so they’re not that bad… and that was sort of the straw that broke the camel’s back for me.”

He says South Bank also disagreed with plans for a stage playing dubstep (harder edge music).

“They felt that kind of music would bring out the ‘bad’ sort of crowd in society,” he said.

The South Bank spokesperson said while problems with the main act were based on noise-level concerns, if the event had been feasible a risk-assessment process would have been undertaken to address issues surrounding the music.

Mr Radaza says the South Bank problems were a major set-back because they developed after event advertising and tickets had been prepared.

“As soon as the deposit was paid, I actually went out there and promoted that it was going to be at South Bank… I paid money for the tickets and advertising.

“When they told us all those conditions, we had to find an alternative place, an alternate route… another park to hold it… so all that time spent promoting and organising it got cut short,” he said.

“I would prefer if they’d been upfront from the start about it and said ‘we’re not happy to have you in our area… we don’t know much about Zombie Walk, but it’s not what we’re looking for’.”

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

-

Zombie Walk moves to Victoria Park

Mr Radaza says the Brisbane City Council and Queensland Police Service “actually saved Zombie Walk” by allowing them use Victoria Park.

“I should have been working with them since we started Zombie Walk… they’ve been really good and they’re still helping me now,” he said.

However, while Mr Radaza says there has been some negativity about Victoria Park’s out of the way location, he does not believe it will significantly affect attendance numbers.

“It’s not the route which defines the Zombie Walk… it’s having the right, like-minded people.

“The people that actually know and follow the Zombie Walk, a change in route won’t make a difference… it’s the people … the community we’ve built in the last six years,” he said.

“If I party with 100 people or 100,000, it doesn’t really matter, because I’m having fun with the people I can share the day with.

“And we collect money for charity too, which is always a bonus,” he said.

-

-

Brisbane’s charitable undead

The 2011 Zombie Walk raised around $20,000 for the Brain Foundation, an Australian charity funding research into a variety of brain disorders, although Mr Radaza says he would like to double that amount this year.

Brain Foundation CEO Gerald Edmunds says the Zombie Walk is important not only for raising public awareness of the organisation, but also the importance of brain health and research funding.

“When you think of all the things that can go wrong [with the brain], both in terms of disorders and diseases, it affects many people.

“Brain diseases and disorders count for 45 per cent of the death and disability in Australia,” he said.

“Raising funds for research… leads to earlier and more accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of these diseases.”

Mr Edmunds says the Foundation often sees a spike in website traffic following events like the Zombie Walk, as it attracts the attention of many tourists and passers-by.

Mr Edmunds also says the Zombie Walk has become a “signature event” for the Brain Foundation and has a “happy-go-lucky” link with the idea of “keeping your brain healthy”.

“Many of the other ones that deal with diseases have, say, pink ribbons, but that doesn’t have the same connection as the zombies have with brains,” he said.

Mr Edmunds says the Zombie Walk is a “wonderful event to have in the community” and is something in which Brisbane leads the world.

“Everybody has a great spirit about them… it’s a big community event.

“And for Brisbane, we’re the biggest in the world,” he said.

“They love to act out the whole part… some like to tease the crowd… move towards the crowd and the crowd all backs away from them.

“It’s all good fun in a very good cause.”

Interested in attending the Brisbane Zombie Walk? The event starts at 10am, Sunday, October 21st, 2012 at Victoria Park, Spring Hill. Tickets are $20 general admission & $10 concession. Visit the Zombie Walk site for more information, and keep up-to-date on Facebook and Twitter.

Need inspiration for a zombie costume? Take a look at the 2011 Brisbane Zombie Walk photo album

If you would like more information on brain health or research, or would like to donate, visit the Brain Foundation site

*All photos in this article are from the 2011 Brisbane Zombie Walk and were available under a Creative Commons license. -

Source: garykemble’s Flickr stream

-

Source: garykemble’s Flickr stream

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

-

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

-

Source: garykemble’s Flickr stream

-

Source: cofiem’s Flickr stream

Breaking news or bogus rumour – verifying online material

Posted by Dan James in Online issues, Tools of the trade on September 30, 2012

In the last few years, Twitter (and other social media) has become increasingly important for journalists. It can be where news breaks; it can be used to for story sourcing (it allows direct, quick contact with potential sources and new information, as Spencer Howson pointed out many, many weeks ago) or even pressuring talent.

However, it can also be home to unverified rumour, misinformation or deliberate falsehood. The plethora of “Celebrity XYZ’s death” hoaxes prove this, with Morgan Freeman the latest in a long line of people sent to an early and inaccurate grave via Twitter. And, as I discussed in previous weeks, while journalists need to be speedy, they still need to be accurate and any mistakes are potentially very damaging to a journalist’s (and news organisation’s) credibility (and if they are correcting their errors properly, will be on public display for the rest of time).

Unfortunately, as Susan Hetherington discussed in the Week 8 lecture (the crowd sourcing one – blimey, I’m getting a lot of mileage from that 50 minutes), journalists can’t just dismiss Twitter out of hand – news of both Whitney Houston’s and Michael Jackson’s death did indeed “break” first via tweets.

So how can journalists ensure they don’t get caught in a Twitter (or other social media, or online source) trap?

Incorrect by default

A quick look through the Poynter Institute site pulled up this interesting quote from the New York Times social media producer Daniel Victor.

Essentially, Victor begins, when looking at breaking news, with a “default” assumption that “everything I see is full of crap.” He says he will only tweet/ retweet it himself once it’s fully proven to be accurate. “If I can poke any holes in it, I’m not tweeting it, and I do my best to needle it like hell,” he said.

He says he puts the info through a “verification gauntlet” – evaluating the account by number of tweets and followers, account verification, the poster’s spelling and grammar. Links need to be to reliable website and tweets need to actually reflect the story. There’s a couple of other things he does for quotes and videos as well (check the link for full details).

But is Daniel Victor the only one who does these things? Or do these checks form some kind of “rule-set” for verifying online info?

Twitter rules, ok?

By the looks of it, Victor’s process for verifying online information is pretty similar to how other reputable journalists do it. A quick search turns up a number of good checklists (which I’ll definitely be printing and sticking to the wall somewhere).

Paul Bradshaw, from the Online Journalism Blog, has written a comprehensive, three layer test/ checklist for verifying online information. I won’t try and extensively quote from it, as it’s quite long, but it’s well worth a read.

Essentially, Bradshaw breaks it down into:

1. Content – is the information “too good to be true”?

Is the information recent and is it frequently updated – this might indicate it’s accurate. Though watch out for photo and video manipulation

2. Context – how reliable is the author?

Age of the (Twitter) account, who the person is following (and being followed by), correlation with other accounts, reliability of any links are all relevant questions.

3. Code – how accurate are the websites; are they who they claim to be?

Check the website address and domain name (government departments are usually .gov and sites with .com “offer no guarantees). Run a Whois search and find out who the address is registered to. Look at older, archived versions of any web pages and look for changes.

Obviously, this is quite a brief summary of Bradshaw’s points. The full story has a lot of good examples to follow as well.

Former journalism educator Peter Verweij has written his own “Seven top tips for verifying tweets” – the suggestions are mostly the same, but also adds the idea of “crowd sourcing” the verification (asking your followers whether something seems genuine – I personally think this might be a bit risk), as well as thinking about “damage control” – the risk/ damage that could be caused by publicising or not.

Craig Kanalley, from Media Helping Media, also has a list for assessing tweet reliability (including checking the time stamp for the tweet in question).

Craig Silverman (from Poynter’s “Regret the Error”) has also put together a roundup of various journalists and news organisations’ (such as the BBC) social media verification practices (piece was written for the Columbia Journalism Review).

Between all these sources, I should have enough ideas about how to verify social media claims and information. It might seem like overkill (and I am a perfectionist), but I think the ramifications of reporting incorrect information, or falling for the ever-traditional Twitter hoax, are too great to be ignored.

Talk to your sources (and nobody is foolproof)

A common piece of advice across all the above is to actually talk to your sources. Try and get in contact with them, either physically (phone call etc) or directly through Twitter (if the person has broken some news). Hopefully, communicating directly will give a better indication of the source’s validity.

However, saying that, I feel I must end on a cautionary tale.* Earlier this year, the BBC posted a photo to accompany a story about a massacre in the ongoing Syrian conflict. However, the photo was actually from the Iraq war in 2003. The article is well worth reading and provides an insight into the BBC’s “verification hub” and the thought processes and decisions around publishing information sourced from users. But the fact even the BBC is making crucial errors just goes to show that, as hard as journalists may try to verify their material, mistakes can still be made. We are all fallible. Nobody is foolproof.

*Link retweeted weeks ago by Susan Hetherington, from one of my previous journalism tutors.

Online Crowd Sourcing – getting the public to do our work for us?

Posted by Dan James in Online issues on September 23, 2012

Today’s post is based on last week’s Online Journalism lecture, particularly Susan Hetherington’s discussion about “crowd sourcing”.

Robert Niles from the Online Journalism Review says “crowd sourcing”, in a journalism context, is the use of a large group of readers to report a news story. It’s an old source (2007), but I think the definition is still relevant.

A more recent definition might be this (from this short video) – “Crowd is sourcing is the act of outsourcing tasks to an undefined large group of people or community (a “crowd”), through an open call.”

Either way, crowd sourcing involves, from my understanding, recruiting people from, say, the general public, to help provide information on a large scale, or help on a task that may be too overwhelming for a single journalist (or team of journos) to manage on their own.

Susan pointed out that this isn’t a new idea – the video above mentions that the original Oxford dictionary was, in fact, crowd sourced. “Readers of the English language” were invited to send in words and definitions and they received six million responses. However, it took 70 years to produce the first edition.

At this point, I had flashbacks to a certain episode of Blackadder III (thanks BBC for putting up a couple of clips).

Nowadays, online crowd sourcing can certainly speed things up. Former BBC journalist, and now journalism educator, Professor Alfred Hermida, says Web 2.0 technologies (so social media etc) create an “infrastructure that allows geographically dispersed individuals with common interests to connect and collaborate over the Internet without any central coordination.” He says crowd sourcing allows journalists to “steer the audience by asking for data, analysis or help to cover events or issues.”

What can we crowd source?

Hermida says crowd sourcing can be broken down into three broad layers. Each of these layers, to me, seems to be an increasing scale of reader involvement in the process of gathering and creating news.

1. General Observation – Hermida says this involves collecting data from people about things they come across in their daily life and then aggregating the information. Here, the news organisation is “tapping into the eyes and ears of its audience”.

A very local example which springs to mind is Quest newspaper’s “Magpie Map”. Readers can tweet the location of dangerous, swooping magpies (#magpiemap) and it’s collated into one large map. A very basic example of crowd sourcing, but still very handy for those whose journeys to public transport are plagued by swooping birds this time of year. It also uses Google maps, another handy online journalism tool!

2. Breaking news – audiences are asked to send in their photos, video or eye-witness accounts. Hermida uses the 2004 Asian Tsunami and the 7/7 London bombings as examples – I think we can update that list with the recent(ish) Queensland floods, Christchurch earthquake or the Arab Spring uprisings in the Middle-East last year. Any breaking news will work (I think), if a journalist needs to bring various strands of information together (e.g. the ABC’s coverage of the dispute earlier this year over Brisbane’s Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Musgrave Park).

3. Investigative journalism – readers help to analyse information, “crunch numbers or pore over documents.” Essentially, large amounts of information (that would be too big for a journalist to work with on their own) are turned over to readers and they can go through and highlight anything that seems important. Journalists then need to collate these (potentially) mountains of crowd-sourced information (probably a big enough task in itself).

Both Hermida and Susan Hetherington used The Guardian’s experiment with crowd sourcing in investigating British MPs’ expenses claims in 2009 (which appears to be ongoing even now). By all accounts, this use of crowd sourcing seemed pretty successful, with a massive reader response. Have a look at that last link, from the Nieman Journalism Lab’s Michael Andersen, for some useful hints for a successful crowd sourcing experience (all lessons learned from The Guardian).

On the other hand, other attempts to crowd source have gone horribly wrong for the news organisations in question. In 2011, a large number of Sarah Palin’s emails were released – the New York Times tried to use crowd sourcing to gather information and determine if there was anything interesting. The response was not what they had expected. Here, the way the New York Times went about it landed them some criticism, with readers essentially complaining they were doing the journalists’ work for them.

I think David Zax’s comments (from the link above) are pretty valid, particularly point one – know your audience. In my opinion, what made The Guardian’s so successful was that they were asking readers to do something they had a semi-personal connection with – going through the expenses of their own elected MPs. By comparison, I doubt the majority of Times readers had that same connection with Sarah Palin, particularly at a time long after she was in the running for Vice-President.

At the end of the day, I think crowd sourcing has the potential to be an incredibly powerful tool. However, as Susan Hetherington reminded us – crowd sourcing is only as good as the crowd itself. Journalists will get garbage information or information that has not been independently verified. We still need to do our own checks and balances, because let’s face it.

For each genius that helps us, we’ll probably get a few Baldricks.

Should the New York Times have published a photo of US Libyan ambassador? The ethics of online photo galleries

Posted by Dan James in Coverage analysis, Online issues on September 16, 2012

Advance warning – this post will be mostly opinion on my part. It’s based around something I found that I felt I had to get a few of my own thoughts down.

By now, most of us should be aware of recent events in the Middle-East, and the protests/ unrest that have apparently been sparked by a certain ‘film’…

One of the events that troubled me the most, and the one which I think has had the most media coverage so far, was the death of US Ambassador to Libya, Christopher Stevens.

A few days after, I was (still) reading about it, actively looking for new articles, when I came across this from the New York Times website.

It’s a response from their public editor, Margaret Sullivan, to reader concerns/ complaints about a photo the Time had run in an online photo gallery accompanying an article about overnight events in Libya (the attack on the US consulate)

Now – I hadn’t yet come across the Times article in question (I usually go to the ABC and BBC first), so off I went to check it out.

And I’ll freely admit I found the photo in question confronting and my initial reaction was that it crossed some sort of line. And despite what I’m about to talk about, I still feel a tad uncomfortable about it, which is why I’m not going to link to the photo directly. However, if you need to see the photo for yourself, it’s the final photograph in the picture gallery accompanying the story linked to at the beginning of Margaret Sullivan’s response.

In short, it’s an Agence France-Presse photograph showing “a man, reportedly unconscious, identified as Mr Stevens,” with severe blackening to the face (bruising or smoke damage, I’m unsure).

On the one hand, I understand the reader’s complaints highlighted in the Times’ response. I think it would be distressing for members of Mr. Stevens family to see those images in the media and I also (partly) agree that the story may have been told well enough without that particular photo.

On the other hand, I can understand the Times‘ position. There may be a clear “journalistic imperative” to running the photo – in many ways, the photo is a defining moment in the story the Times is trying to tell. I don’t necessarily agree with the argument that they run photos of “Iraqis, Syrians” dead etc, so why not the ambassador. While there are plenty of photos of civilian casualties, I don’t think many of them feature the victims in such a face-on close up.

However, what this incident does highlight for me is the benefit of an online photo gallery. The photo was run “in the last position in the frequently updated gallery, where it would be less prominent.” Thus, reporting the story online allowed the Times to still run their potentially controversial photo, but not give it the full emphasis that a front-page printing would – which I think would have been insensitive and certainly have overstepped the line. Margaret Sullivan says she would not want to see the photo on the front page, where “its prominence and permanence would give it a different weight” (although, in my opinion, an online gallery makes it potentially even more permanent).

At the end of the day, while I still find photo’s publication slightly uncomfortable, I agree with the Times that an online gallery was the most suitable and ethical place to run it. I certainly prefer it to running it on the front page, which I believe some other news organisations did. It should also be noted that the Times did not go on and print it on the front page the next day.

As an aside, here’s the Times‘ response to a request from the US government to remove the photo – I think it’s good to see a news organisation “sticking to its guns” once it has made a decision (though if it had been an even more graphic photo, I think the removal request would be justified).

Live Blogging vs Live Tweeting

Posted by Dan James in Coverage analysis, Online issues on September 9, 2012

Oh dear… I appear to have missed last week’s post. Curse property law assignments! However, now that I’m free of leasehold covenants, rent guarantees and indefeasibility for a couple of weeks – on with the blogging!

Today, I thought I’d take a brief look at live blogging compared with live tweeting, and why one might be preferable to the other.

Live blogging

According to Daniel Hurst, from the Brisbane Time, live blogging involves “ditching the normal news structure”. Journalists instead provide regular, short updates on a continuous news story. He says they can be used to cover a wide variety of stories, including:

– unfolding political stories, debates and elections

– severe weather events

– sporting matches

– riots and protests.

Essentially, Hurst said live blogs can be used for any topic in which an audience will be interested in ongoing updates. He also said running live blogs for rapidly unfolding events makes it easier for readers to digest “bite-sized” pieces of information and that it’s easier for journalists to write short, sharp updates. The Guardian’s Matt Wells makes some similar comments here.

It was also pointed out to us that live blogs can sometimes take a more conversational tone (though I’d assume the context of the news item in particular would determine if this was appropriate). For example, check out the ABC’s live blog coverage of the Olympics Closing Ceremony – possibly the best example of a “conversational tone” I’ve seen. Obviously a more “light-hearted” story like the Closing Ceremony could allow you to be personal and less serious, as compared to say, live-blogging a natural disaster.

The other main benefit of live blogging that Hurst discussed was that it developed a two-way conversation with the reader – journalists can include social media (and other interactive media) to show reactions to news, as well as excerpts of analysis and comments from (and links to) other articles (even their competitors!).

However, live blogs don’t necessarily work for every story. Channel 4’s technology correspondent Benjamin Cohen (quoted in Matt Wells’ piece above) says live blogs need a “lot of content to work” and also only really work if journalists have a big audience to read and share it. He says they can also be confusing for new readers (because of the amount of content) and thus need continual “signposting” – good curating and management are to prevent a live blog becoming a “mishmash of tweets and comments with context.” Finally, I find it interesting that Cohen also says, for some breaking stories, it’s actually more interesting to look at the Twitter stream for a breaking story – which leads nicely into my next point.

Live Tweeting?

Many people will be familiar with the idea of live tweeting – follow any journalist or news organisation on Twitter and, when they attend a press conference or breaking news event, you can be sure there’ll be a constant stream of updates letting the reader know exactly what’s going on (as best they can in 140 words). The Poynter Institute’s Herbert Lowe describes live tweeting as a “standard tool” for breaking news.

However, Daniel Hurst was sceptical about live tweeting press conferences, and another Poynter Institute author, Matt Thompson, has given five (in my opinion) convincing reasons why a live blog might be better.

Firstly, Thompson does admit Twitter has some “key advantages”, namely that the software is easier to use (no live blogging client to try and embed in your site) and that it also allows you to engage with everyone who follows you (not just those visiting your site on a regular basis).

But he also points out that Twitter’s 140-character limit makes it difficult to capture the “flux of a speaker’s argument, or the back-and-forth in a panel discussion.” It is good for tweeting “applause lines” though.

Of Thompson’s five points, I think the first two that running a live blog forces journalists to pay attention and forces them to write – warrant some discussion. I’m not 100 per cent sure doing a live blog will force journalists to pay more attention. I suppose you could argue the increased amount of information needed (or provided?) by a live blog means journalists would pay attention so they can write more (with the flipside being live tweeting journalists only looking/ listening for main points). However, I think a live tweeting journo would still need to pay attention to all the information, so that he actually knows which pieces are the most important.

Thompson’s second point is something I could agree with entirely. I’ve already mentioned, in my Speed vs. Accuracy post, that I’m a bit of a perfectionist. I like the suggestion that the continual pressure of needing to provide longer updates every few minutes stops journalists from fretting over every word and sentence. Hopefully, doing some live blogging might help break me from this habit. Conversely, I think trying to live tweet something might make me more pedantic, as I try and condense all my ideas down into 140 concise characters.

Correcting errors in online journalism

Posted by Dan James in Online issues on September 2, 2012

A recent report on the ABC’s Media Watch program about the reporting around Julia Gillard’s latest battles with the media got me thinking about how journalists go about correcting errors they may have made in their stories.

In this instance, the Australian made (in the print versions of their publication) “minor errors with major consequences,” according to Media Watch. To correct them, they published two online statements acknowledging the mistakes had been made. However, I notice that the corrections go no further than merely stating that certain claims were “wrong” and “are untrue”.

But in the online world, where the news moves so fast and stories are constantly updated, wouldn’t it be easier (and is there a temptation to) simply delete/ fix errors, sweep them under the carpet and pretend they never happened?

Common errors

While I think all journalists try their best to avoid errors, it’s probably unavoidable that some slip in from time to time.

According to Mallary Tenore, from the Poynter Institute, misspelled names are the most common errors. For example, of the 56 corrections Poynter had run this year (as of May 12, 2012), 16% were apparently name misspellings. The article quotes similar statistics for other news sources (e.g. 16% for the New York Times and 14% for the Los Angeles Times)

Corrections also need to be run for any incorrect assertions or misquotes, according to another Poynter Institute writer, Craig Silverman. Silverman runs the Poynter Institute’s Regret the Error page(s), which “tracks accuracy, errors & the craft of verification”. It’s well worth checking out (and isn’t limited to American news).

At the end of the day, no matter what the error is, I think it’s vital that journalists try to correct them as soon as possible. Otherwise, how can we claim to be a credible, trustworthy source?

Transparent correction

But what is the best way to correct errors journalists may have made? Unsurprisingly, deleting errors and pretending they didn’t happen isn’t the best way to go about it.

Rudy Lee, from the Ryerson Review of Journalism, says a good corrections policy starts “with the understanding mistakes are inevitable,” and that transparency is the key.

The Canadian Association of Journalists has outlined some best practices in digital accuracy and correction. In particular, they have three core principles that I think any online journalist would do well to remember. I’ll briefly repeat them below:

1. “Published digital content is part of the historical record and should not be unpublished. News organisations do not rewrite history or make news disappear.”

2. “Accuracy is the foundation of media credibility…. we should resist unpublishing… we should publish corrections or update online articles as soon as we verify errors.”

3. “Transparency demands that we are clear with audiences about changes that have been made to correct/ amend or update digital content. We should not “scrub” digital content, that is, simply fix it and hope that no one has noticed.”

The best way (and probably most logical way) to do this is to have a dedicated corrections page for each news organisation. According to all the sources mentioned so far, this will help maintain credibility as journalists acknowledge their mistakes and, in doing so, assure readers that they are committed to accuracy.

For example, both the BBC and the ABC have their own dedicated corrections pages (both of which can be found by a quick Google search). A quick glance at the page(s) allows a reader to see a complete history of all corrections that have been made (and importantly, an explanation of what is was wrong, not just “it was incorrect”).

Many news organisations also insert a note into a story, either at the beginning or end, to inform the reader that corrections have been made.

I particularly like the way the Columbia Journalism Review handles their corrections. Not only do they have a dedicated corrections page, but they also put a strike through the original error, with the correction immediately following. I quite like this, as I think it makes it very, very clear to the reader exactly what information has been changed (and they can see the changes visually at a glance, without needing to compare an old and new version of the story). Finally, they also include a “Report an Error” button at the end of every article. This will make it even easier for news organisations to have errors brought to their attention, as helping reader report errors makes them all into fact checkers (according to the Canadian Association of Journalists).

Unfortunately, not every news organisation seems as open. I had a look around the Courier Mail’s website and was unable to find a corrections page, or even any clear instructions/ guidance about what to do if a reader finds an error. If anyone else is able to find such a page, please let me know and I’ll correct this. Knowing my technological skills, I might have missed it.

In summary, I guess there are three keys things I need to remember:

1. Mistakes happen, but don’t just delete them

2. Be open and transparent about errors and corrections (and try to fix them quickly)

3. Make it easy for readers to find corrections that have been made (and easy for them to get in touch about mistakes you’ve yet to find)

Coverage Analysis – Lance Armstrong’s announcement re: USADA

Posted by Dan James in Coverage analysis on August 26, 2012

Well, what a news day Friday 24th August was. We had former Bundaberg surgeon Jayant Patel’s conviction overturned (and a new trial ordered) by the High Court, Norwegian killer Anders Breivik declared sane and, in the cycling world, the news that Lance Armstrong had decided to end his battle against the United States Anti-Doping Agency over doping allegations.

It’s this last story that I’ve chosen to do a coverage review on, for several reasons.

- As a law student, I don’t think could cover the first two without getting side-tracked into legal analysis (which isn’t really the point of this blog).

- The Armstrong story was the first time I’ve actually seen a story break on Twitter before my eyes (as in, one moment nothing, then whoosh – news!) and I followed the ABC story as it was written and updated.

- I used to watch the Tour de France in the Armstrong days, with my father, and he was/ is one of the few athletes I’ve come close to semi-admiring. So the story had a tiny bit of personal connection for me.

For this review, I’ll be comparing the coverage of two news sources: The ABC Online news story, and the article posted to the Courier Mail’s online site later that day. I will also be loosely judging the stories based on a few of the Dozen Online Writing Tips, suggested by Jonathan Dube, from Cyberjournalist.net and the Poynter Institute.

1. ABC Online story

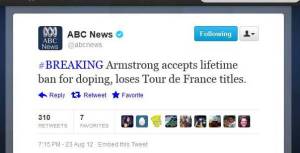

Here’s the tweet which first alerted me to the story. I was idly browsing Twitter when it popped up in my news feed.

And here’s a clarification tweet that came up a bit later. Take note of the clarification – as one commenter said, it really is almost a completely different story. I suppose this is a good example of “Speed vs Accuracy” at work. But at least the first tweet told me the story had broken AND the ABC did clarify/ correct the error pretty quickly.

And here’s the article that appeared on the ABC’s website. There wasn’t a link to it from their Twitter feed, but I knew once I saw the tweet that I could head over to their website. I was actually there before the article was put up.

As I mentioned previously, I literally watched this story come together over a few hours. It started with a very basic couple of sentences breaking the news, and then I watched as more detailed was added (until the full story was up by the time I got home)

Overall, I think this story is the better of the two, for two main reasons:

1. The ABC has (in my opinion) the better story.

At just a quick read, the reader is able to understand the gist of Armstrong’s statement and why he has made his decision. However, the USADA’s position is put forward to counterbalance, with quotes from the USADA chief executive. Further, the entire USADA’s case is outlined in the fact box, which helps present their side of the story.

Overall, the article is probably more biased in favour of Armstrong. He’s the most extensively quoted person, though this may be because the author seemed to be at the announcement (the way the story went together showed me a good example of how a running story pans out).

The story’s lead is nice and clear and there doesn’t appear to be any instances of “pile on”. Although the story was continually updated with new information, the article remained perfectly understandable for new readers (see hints for online writing #6 & 7). It also neatly follows conventional journalistic structure, with the most important information at the start, with everything under the pull quote as background information for the interested reader.

Finally, the story is a good length. Once the fact box is taken out, it’s just under 700 words, which seems a good length (hint #8 suggests keeping stories under 800, as a guide).

2. The ABC has told the story well.

They’ve clearly thought about how to best ‘Tailor their news gathering’ (see hints for online writing #3) to tell the story.

I think there is excellent collaboration between the writing, visual and interactive elements. The completed article has a nice picture slideshow (mostly of relevant images from his Tour de France wins). The USADA’s case against Armstrong is comprehensively outlined, but in a summary box next to the article, so the main story isn’t burdened with the extra detail. It ends with a few links to Youtube videos of Armstrong’s cycling career (which I thought was a nice touch). There are also links throughout the article to other relevant stories, and importantly, the link to Armstrong’s statement is in the first couple of paragraphs.

If there’s one criticism I have of the layout, it’s that it could maybe be broken up better (the paragraph spacing could be bigger), although the addition of the pull quote gives the reader a place to pause. There’s also a link to a Google Map of the United States, with (I’m assuming) the location of Armstrong’s press conference marked? I’m not really sure that this adds anything to the story.

2. Courier Mail online story

Note: The Courier Mail may have posted an improved/ different article later. However, I selected this article, as it was the one first linked to in their twitter feed and the one used to break the story.

Overall, I don’t think this article provides particularly outstanding coverage. There are several reasons for this:

1. The headline is inaccurate (at least in my opinion).

It states “USADA strips Lance Armstrong of Tour de France titles.” As far as I am aware, when the article was written, he had not been stripped of his titles (leaving aside questions of whether the USADA actually has the jurisdiction to do so…)

2. The story itself

The article is written strangely and is awkwardly organised. The actual article seems to finish just above the sub-heading “Lance through the heart”. My eyes actually skipped over/ didn’t register the little “-AFP” indicator at the end of it when I read through the first time. The rest of the story appears to be a mix of commentary and reporting from a different author – Philip Hersh from the Chicago Tribune.

However, it’s the overall tone and viewpoint of the article I have the most issues with. The article seems very pro-USADA/ anti-Armstrong. The USADA’s voice and opinion features most strongly and Armstrong doesn’t even get a say until very near the end. The link near the end to Armstrong’s statement almost looks like an afterthought. Also, there seems to be a bit of “pile on” happening in the latter half (see Dube’s hints for online writing #7). A paragraph about other Tour de France winners/ cyclists who have been caught for doping appears before the information about Armstrong’s statement. While this ordering isn’t a “pile on” of “new” information (as the Tour de France background is older news), I still think it creates an awkward mish-mash of the story.

Also, some of the reporting and commentary hardly seem impartial: “But he officially will be known as a doping cheat forever,” and “Armstrong’s statement was still filled with the arrogance and bravado that marked his post-cancer cycling career.” The first video does help provide a little more background for Armstrong’s side of the debate, but not much. However, the article ultimately does seem to cover the story from the USADA side.

The article also might run a bit too long – it’s nearly 1,000 words.

3. The layout

I think the Courier Mail could have done a bit better at breaking the story up. There’s a lot of text to read and very little else. The one photo of Armstrong and a single heading – no charts or tables that might be useful in summarising information (as suggested by Jonathan Dube’s 9th tip for online writing). The standfirst at the beginning of the story doesn’t actually summarise its content, instead linking the reader out to other articles. I don’t think the videos really help to “break up” the story either, given they’re placed before it. There is a link to a larger photo gallery, but it takes you to the Herald Sun’s site.

Overall, it doesn’t look like the Courier Mail put a large amount of time and resources into this article. Perhaps this is understandable, given that August 24th also saw a massive local story break (Jayant Patel’s High Court victory), which the Courier Mail did cover extensively. Jonathan Dube’s first online writing tip is to “Know your audience.” As the Courier Mail is primarily a Queensland newspaper, it makes sense they would given more attention to the Patel decision.

The battle between Speed and Accuracy in Online Journalism

Posted by Dan James in Online issues on August 18, 2012

In the wake of this week’s “speed vs. accuracy” exam for QUTOJ1 students, I’ve realised one major thing.

…I’m something of a perfectionist…

By this, I mean I probably spend far too much time considering every sentence, trying to ensure each sentence imparts as much information as possible. I’m also someone who will (usually) try to double check (or even triple check) any facts before I commit them to the page. In essence, I want to make each sentence as an efficient use of words and page space as possible.

Which is probably, as it turns out, a somewhat inefficient use of my time*

But at least I’ll get good marks for accuracy. Right?

However, I do understand the need for speedy writing in journalism, particularly in the online sphere. The news moves so fast nowadays, particularly in the era of 24-hour news channels. We are constantly being reminded that, in today’s world, “the deadline is now.”

Life in the fast lane

But what exactly is driving this “need for speed”

Kendyl Salcito, from the Centre for Journalism Ethics (at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) says the proliferation of news outlets – “bloggers by the millions… but also cable… satellite television” has led to a “multi-media race” to get “the story 24-hours a day. She notes that the public has an increasing demand to see news “as it happens”, particularly for coverage of natural disasters or other breaking events.

However, Salcito also says that “as the pace intensifies, so does the pressure to cut corners,” and that “laziness, lack of rigor and other bad habits” can complicate the ethics of speed and accuracy.

Ironically enough, the public that were hounding journalists for speedy information also expect the news media to create accurate and verified reports.

Oops!…

Former Washington journalist and journalism lecturer, Don Campbell, gives some good examples of errors that have occurred when journalists were too hasty (and perhaps merely repeated internet rumour without verification…). For instance:

1. Reporting Arizona congresswoman Gabrille Giffords as deceased after being shot in the head. She in fact survived.

2. Reporting an American governor was facing a federal indictment on tax charges. However, he didn’t have any evidence to support his claim and Campbell describes this as clear “character assassination”, with the blogger responsible putting “speed ahead of the basic principles of accuracy and verification.”

However, something Campbell found more troubling was that credible news organisations (e.g. The New York Times or Washington Post) ran one of these inaccurate stories on their online sites. This is the most troubling thing to me – if even these large, respected media organisations are putting speed before accuracy, I do wonder what future there is for someone like me who obsesses over detail?

Fastest fingers in the West?

At the end of the day, I think it’s a fine balancing act I’ll definitely need to learn to walk along (and quickly). However, I still think my somewhat pedantic attention to detail has a place – just maybe not in an online newsroom.

I think Salcito’s article gives me a good question to ponder:

“How much accuracy is too much, when news must be current?”

Or maybe I should just type faster?

*EDIT: my woeful (i.e. “no”) marks for speed prove this!

Am I going to get paid for this? Paywalls and Online Journalism

Posted by Dan James in Online issues on August 11, 2012

At the moment, the answer seems to be – probably not.

A recent online journalism lecture served as quite a wakeup call for many of my fellow students (and confirmed my own fears) about the current state of the journalism industry.

John Grey, former online editor at the Courier Mail, used a somewhat depressing Titanic analogy to describe the reaction media organisations have had to declining newspaper sales and the move to an “online future”.

“They’re not just rearranging the deckchairs, they’re throwing everything overboard.”

But before we all sink any further into the icy waters of despair, it’s worth noting consumers clearly still want our product. The following graph, using information from a Ray Morgan poll (and referred to in the Week 2 lecture) shows traffic to online news sources has grown very steadily over the past couple of years.

Further, it could also be said readers still want their news from the same familiar sources, that there remains a certain brand attraction (or loyalty) to specific news outlets. A 2012 “State of the Media” report by the Pew Research Centre’s Project for Excellence in Journalism found searches on (in?) the news outlet itselfwere the “most popular path to the news” (followed by general searching of the web).

However, even though people still want the news, the news organisations themselves are struggling to figure out how to make this pay. According to John Grey, the current online news model is free content, supplemented with advertising revenue. While there are many different ways of raising revenue online (charging properly for online advertisements, website registration with demographically targeted ads, metered access to websites), the most common method appears to be the construction of a “paywall”

Why have paywalls?

According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, a paywall is “an arrangement whereby access is restricted to users who have paid to subscribe to a website.” That little definition was added in 2010. Many news organisations are now making readers pay for online content – most notably big American newspapers like The New York Times and in Australian, local heavyweights like The Australian and Herald Sun.

For the New York Times, the paywall seems to be working, appearing to be partially offsetting the fall in revenue from their print publications. Steve Ladurantaye, a media reporter from The Globe and Mail, said the Times was expecting to earn $85 million from its nearly half a million online subscribers this year.

However, it should be noted that the Times paywall allows non-subscribers access to 10 free articles a month. Ladurantaye also says this “metered” system is becoming the preferred method of online publication. Carrot, then stick, I guess? Maybe “bait” is more appropriate.

Online media advocated and associate professor at New York University says the Times metered method has been working because it can target both dedicated and casual readers.

“We will never get a majority or even a sizeable minority of our readers to pay use directly, but we can design a system in which some of our most passionate, engaged readers pay us directly, and the rest of the readers, the casual readers, we can keep around for the advertising revenue,” he said in an interview earlier this year.

Closer to home, the Australian’s paywall also seems to be working, with around 40,000 subscribers by March 2012.

The other side of the argument

Not everyone is happy with paywalls.

A recent survey suggests only one in four new media professionals believe a paywall increases a company’s revenue. Maybe more alarming for news organisations, the survey also found more than half of the participants said they immediately left the site when they encountered a paywall. However, around 40% did say they at least considered a subscription purchase (and 22% said they tried to find some way of cheating the system).

I also find it interesting that even those who are training to be journalists are often turned away by a paywall. While that article is anecdotal evidence, with a very small sample size, I personally can’t help but feel it’s a good indicator of what might be happening. I know myself that I will often leave a news site once I’ve hit my free-article limit. It’s for that reason that I usually visit those organisations that don’t have a paywall (most notably the ABC, for obvious reasons). So if even journalism students are being turned away by paywalls, I can’t help but wonder how viable they are in the long-term.

And not every news site that erected a paywall has stuck with it. A large regional daily newspaper in the UK scrapped its paywall earlier this year after only nine months. However, it did replace it with an iPhone app, which suggest there may be plenty of other ways to get readers to buy content online.

Finally, but of the most concern to me, it’s also been suggested that paywalls will change the way journalists write. According to journalist Tim Burrowes, the traditional format (pyramid structure, layering of information etc) doesn’t work for “paywall journalism”. He says that as most paywalls allow the reader to see the headline and first couple of paragraphs, before asking for payment, the traditional model doesn’t prompt people to subscribe (as they’ll have gotten the most important information anyway). Instead, introductions need to written to intrigue the reader, or be deliberately vague and only get to the point in the 3rd paragraph (which is safely ensconced behind the paywall).

However, Burrowes says this new method of writing is dangerous as it fails to put the reader first and could perhaps drive readers away.

“Each time creates a minor annoyance, until the reader starts to subconsciously associate that with the publication in question,” he said.

For me, this seems the most alarming thing about paywalls. Asking for payment is one thing – needing to deliberately compromise your writing styles and key journalistic principles seems far worse.

I’m sure there’s a better way to make online journalism pay (but I don’t have any ideas). I just hope they find it quick.

comments